Rare Earths Export Controls: are in the news again. In October 2025 Beijing quietly rewrote the materials rulebook.

The latest rare earths export controls don’t stop at oxides and separates; they extend to technologies, alloys, and even finished goods that contain rare earth elements. This isn’t about geology. It’s leverage.

What changed

China’s Ministry of Commerce expanded export controls to require licences for products containing even trace amounts of Chinese-origin rare earths. Defence end-uses are effectively off-limits; semiconductor applications face case-by-case reviews.

Cross-border collaboration involving Chinese rare earth inputs or technology now needs prior approval. It’s a foreign-direct-product-style rule for materials, and it pushes compliance risk onto every company that relies on neodymium, praseodymium, or dysprosium in motors, generators, sensors, or chips.

How we got here

Deng Xiaoping framed the strategy more than thirty years ago: “The Middle East has oil; China has rare earths.” The long game wasn’t just mining. It was mastering separation chemistry, alloying, and magnet manufacturing—precisely where the bottlenecks live today.

That’s why having a mine in California or Australia doesn’t grant independence: concentrates still had to move through Chinese separators to become useful materials. The result is dominance in processing and magnets that reaches into every EV, wind turbine, and phone.

Consequences you can feel

The new rare earths export controls regime means provenance moves from marketing footnote to legal liability. A magnet plant in Europe or Japan must now justify non-Chinese upstream feed to stay on the right side of export licences. Even when supply is available, the licence paperwork, audits, and re-routing add friction and cost—the hidden tax on time and capital.

Policy is trying to catch up. Europe’s Critical Raw Materials Act sets 2030 targets for extraction, processing, and recycling inside the bloc or trusted partners. The U.S. is funding domestic capacity through a patchwork of tax credits, defence spending, and state-level incentives. But timelines are long, and the chemistry is unforgiving. Meanwhile the controls bite now.

Who’s moving—and what it tells us

In France, Solvay has restarted and expanded its La Rochelle lines to deliver rare-earth materials for permanent magnets—Europe’s first serious step back into this space.

In the U.S., MP Materials has stood up its Fort Worth facility to make metals, alloys, and finished NdFeB magnets, and USA Rare Earth is pushing an integrated mine-to-magnet chain.

Australia’s Lynas is deepening magnet supply into the U.S. through a tie-up with Noveon. These are early signals that the West understands where the leverage sits: separation, alloy, magnet—plus provenance.

The recycling opportunity

Recycling is the most pragmatic hedge. In Canada, Cyclic Materials is building a Kingston centre for magnet feedstock recovery, with a sister hub in the U.S. Heraeus Remloy has opened Europe’s largest magnet recycling plant in Bitterfeld, targeting 600 t/yr with room to double.

REEcycle in the U.S. reports very high recovery rates from scrap magnets. And the OEMs are leaning in: Apple and MP Materials announced a $500m programme to produce recycled magnets in the U.S., pairing circular feedstock with domestic manufacturing.

Recycled material often beats primary supply once you price in logistics and compliance risk. More importantly, it’s politically defensible—and it doesn’t depend on a licence stamp thousands of miles away.

Alternative magnets and new chemistry

At the frontier, new materials are moving from papers to pilot lines. Niron Magnetics is scaling iron-nitride magnets that remove rare earths entirely, backed by U.S. industrial credits and a new Minnesota plant. Proterial (ex-Hitachi Metals) has introduced heavy-rare-earth-free neodymium sintered magnets designed for EV traction motors.

On the research path, Cambridge-led teams are developing tetrataenite, the so-called “cosmic magnet,” which could eventually act as a gap technology between ferrites and NdFeB. None of these remove the need to build conventional capacity now, but they change the slope of dependency.

What to do—now

- Map exposure with precision. Treat every magnet as a provenance problem: magnet → alloy → separated oxides → mine. Document it. Audit it. Build a view of where licences would bite.

- Write better contracts. Add audit and substitution rights, origin warranties, and pricing mechanisms that survive export denials. Build pre-qualified alternates into framework agreements.

- Back recycling at scale. Secure offtake with recyclers; help them finance capacity against your demand. The economics are improving, and the politics already work.

- Invest selectively in the bottleneck. Equity or JV positions in separation and alloy lines buy optionality that paper contracts can’t. Co-locate with grid and logistics.

- Place early bets on substitution. Line up trials with iron-nitride and reduced-Nd compositions for non-safety-critical applications first, then scale by performance.

- Work policy like it matters—because it does. In Europe, tie CRMA (Critical Raw Materials Act) targets to real permits, grid connections and tax. In the U.S., use federal tools to de-risk magnet plants, not just mines. Alignment beats slogans.

The long view

Deng’s line wasn’t bravado; it was a blueprint. Today’s rare earths export controls lock in the idea that control rests where materials become machines.

The choice for Europe and the U.S. is straightforward: build processing, magnets, and recycling, or keep asking for permission. The technology exists. The talent exists. What’s required now is focus—and the will to move faster than the paperwork.

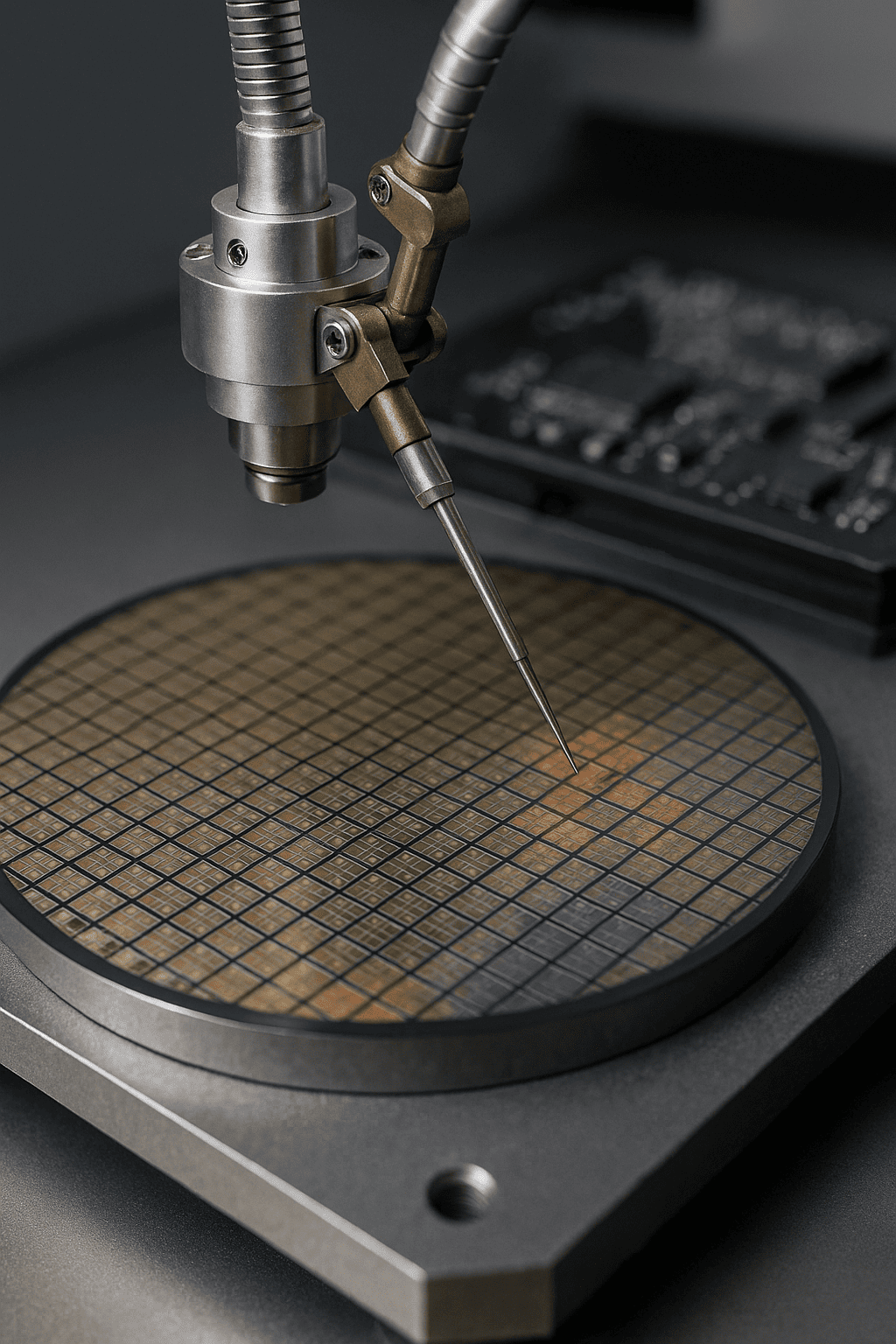

The bottleneck isn’t ore. It’s separation, alloying, and magnet/wafer capacity.

FAQ: Rare Earths Export Controls

What do China’s new rare earth export controls cover?

They extend beyond raw oxides to technologies, equipment, and finished goods that contain rare earths. Defence and semiconductor uses face denials or strict reviews.

Which sectors are most exposed?

EV traction motors, wind turbine generators, precision sensors, and parts of the semiconductor and defence supply chains that rely on NdFeB magnets.

What can companies do now?

Map provenance, add audit/substitution rights to contracts, secure recycling offtake, invest in separation/alloy capacity, and pilot alternative magnet materials.

Are there viable alternatives to rare earth magnets?

Iron-nitride magnets (e.g., Niron) are emerging for some use-cases, while reduced-Nd and heavy-rare-earth-free compositions from established players are progressing.

Does recycling meaningfully reduce risk?

Yes. Closed-loop recovery of NdPr and heavy REEs from end-of-life motors and electronics provides local feedstock and reduces licence and logistics exposure.